Winter air pollution in India and Pakistan

In this blog, we break down the science behind why winter pollution becomes so devastating and explore some of the emerging solutions India and Pakistan are using to tackle it.

A perfect storm

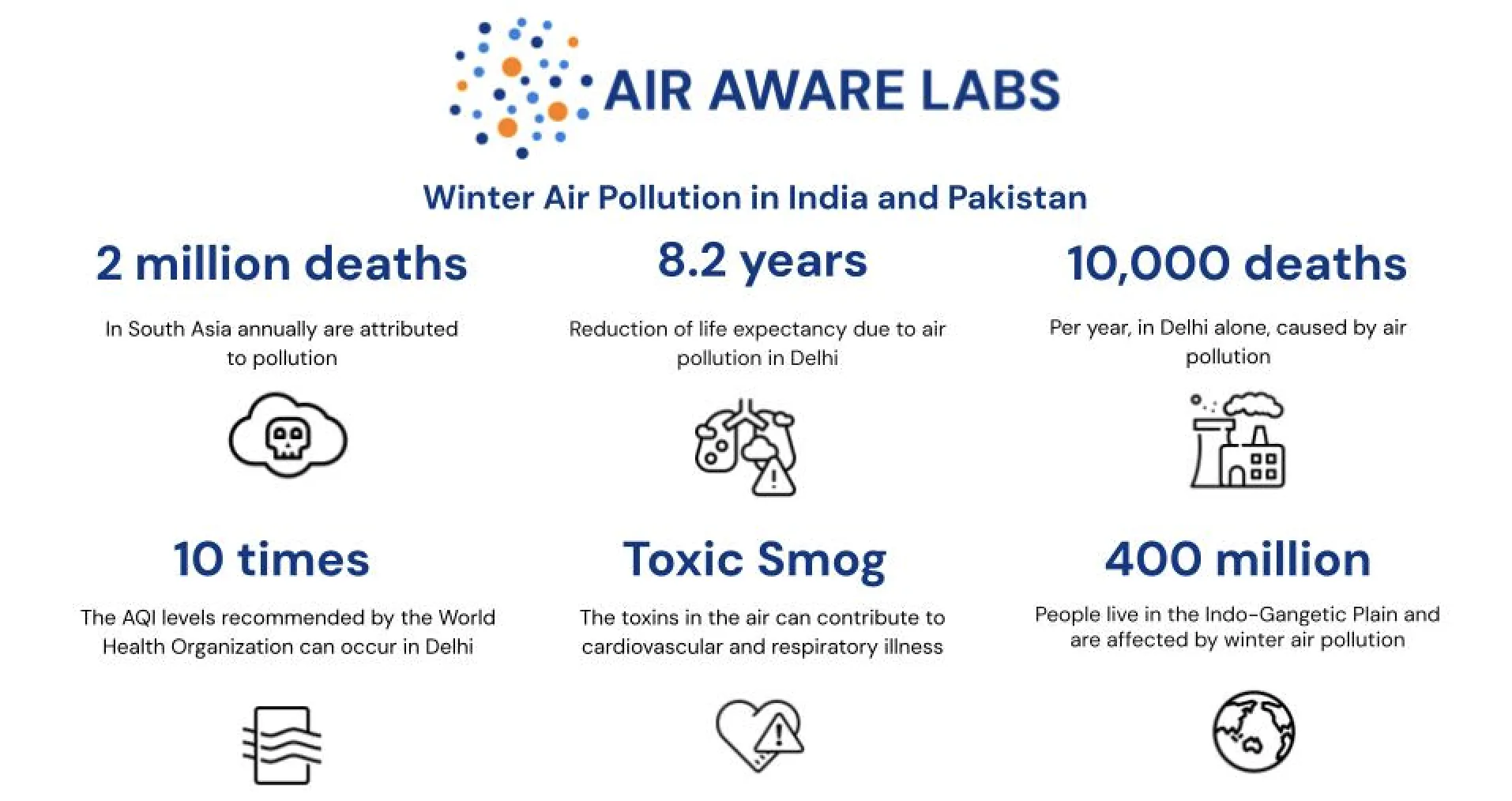

Covered in a blanket of thick smog, each winter South Asia falls into a familiar, yet dangerous, pattern. Cities like Delhi and Lahore, already ranked among the world’s most polluted, see their air quality plunge alongside the temperatures. Ranked as the most polluted capital four consecutive years, Delhi’s winter air quality, measured on the Air Quality Index (AQI), can exceed 500. This value is shocking considering the World Health Organization classifies an AQI below 100 to be safe. Similarly, Lahore’s air is labeled as "hazardous" for fine particulate pollution (PM2.5) on the AQI scale.

This annual spike cannot be blamed on one single source. Rather, it is a perfect storm combining factors like cold and stagnant weather, the bowl-shaped geography of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, and a surge in seasonal emissions from crop burning, firecrackers, biomass heating, and heavy urban pollution. The consequences of these conditions are severe, being linked to the region's higher rates of cardiovascular and respiratory illness. In Delhi alone, pollution is estimated to contribute to around 10,000 premature deaths each year, while the rest of South Asia faces nearly 2 million pollution-related deaths each year.

Why pollution worsens in winter

The winter pollution in India and Pakistan is a result of meteorology, geography, seasonal human activities, and urban sources, which create the perfect conditions for toxic smog. The first factor to consider is temperature inversion, or where a layer of warm air sits above the colder surface air, trapping emissions close to the ground, ultimately, preventing pollution from dispersing. During inversion periods, scientists note that emissions from industry, vehicles and crop burning have “nowhere to disperse.” Other factors such as low wind speeds and cooler temperatures reduce the natural ventilation even further, meaning that the pollutants build day by day.

Geographically, the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the home of Delhi, Lahore, and millions of people, is surrounded by mountain ranges which naturally trap pollution, creating what experts call “airsheds” that can span multiple states and countries. Polluted air settles into the basin and stays stagnant during the winter months.

Seasonal activities amplify these effects. During the winter months, farmers begin crop burning, rushing to clear their fields for the next planting season. This results in a spike of PM2.5 and PM10 quantities, which blow into Delhi and Lahore. Firecrackers during the festival of Diwali along with household biomass heating add to the black carbon emissions, worsening the air quality and health risks.

Urban sources further compound winter pollution. Traffic congestion, especially from diesel vehicles, and diesel generation, used during power shortages, contribute to the increase in PM2.5 and PM10. Construction dust from roads and building sites is more prone to being trapped in the stagnant winter air, which prompts temporary bans during peak smog season. Despite authorities' best efforts to reduce these effects, such as intensified street cleaning and regulation on diesel operations, the combination of dense traffic, industrial activity, and construction remains a large contributor to the winter smog.

Current responses

Both India and Pakistan have taken steps to reduce their winter air pollution, though challenges remain and the smog persists. In Delhi, the Graded Response Action Plan, or GRAP, is activated when the AQI reaches a range of 301–400 (“hazardous”). This plan outlines actionable steps such as construction bans, vehicle restrictions, intensified street cleaning, water sprinkling on roads, and regulated diesel generator use. Forecasting systems from the India Meteorological Department and the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology guide pre-emptive actions, while citizens are encouraged to reduce private vehicle use, avoid open burning, and follow other GRAP recommendations.

In Pakistan, Lahore has made progress through stricter enforcement of anti-smog measures such as early market closures, fines, and drone-monitored industrial inspections. These measures reportedly helped AQI drop from 390 to 125 in early November 2025. Although these numbers show a sizable shift, the Pakistan Meteorological Department states that favourable weather conditions contributed to the improvement, meaning that the smog may return once they shift.

Although some progress is visible with better monitoring and enforcement, gaps remain. Long-term industrial reform, consistent enforcement, and cross-border coordination are crucial. Pollutants travel far from their sources across South Asian airsheds, so isolated city-level actions are insufficient.

Emerging tech solutions

New technologies and solutions are available to help individuals monitor and manage their air pollution exposure. Apps like AirTrack provide personalised exposure scores and suggest “clean routes” to reduce inhalation of harmful particles. These types of behaviour nudges have been shown to lower personal exposure to air pollution in Delhi by 40–70%, with higher exposure reduction percentages observed in Bangalore.

Several other initiatives are working to tackle air pollution in India and Pakistan through technology and research. The Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago developed the Air Quality Life Index, a tool which translates air pollution levels into their effects on life expectancy. This helps policymakers and communities understand the real health costs of pollution and design evidence-based interventions. It shows that the average Indian citizen loses 3.5 years of their life because of air pollution. Shockingly, those in Delhi live 8.5 years less than if pollution levels met the World Health Organisation's outline.

The Air Pollution Asset-Level Detection, based in Oxford UK, uses machine learning and geospatial analysis to detect and identify pollution sources, particularly brick kilns in the Indian-Gangetic Plain, and map their environmental impact on nearby populations and ecosystems. Together, these three efforts show how data, health research, and technology can drive more targeted and effective air quality solutions. Predictive modelling systems and smog forecasting allow authorities to implement pre-emptive measures, which help to reduce health risks before pollution peaks.

Within cities, clean mobility initiatives such as electric buses, low-emission zones, and incentives for cleaner vehicles, have been shown to improve air quality. Even more innovative solutions to reduce crop burning, such as mechanised residue management and subsidised bioenergy alternatives, demonstrate how, together, technology and policy can limit seasonal emissions effectively.

What’s needed next

To achieve lasting improvements, human-centric exposure data is essential. Average city AQI alone does not fully reflect the risk experienced by individuals. By linking exposure metrics to health outcomes, such as asthma attacks or heart-rate variability, targeted interventions can take place. The widespread adoption of monitoring apps like AirTrack can help scale these benefits.

Equally important are city and regional partnerships, as well as increased education on the issues surrounding air pollution. The Lung Care Foundation, a Delhi-based non-profit founded in 2015, focuses on improving lung health nationwide through education, clinical care, and research which continues to explore the environmental impacts on respiratory health. These coordinated approaches between municipalities, health agencies, and technology providers can reduce pollution and ensure interventions benefit people on a larger scale, not just within singular communities.

Conclusion

Winter pollution in India and Pakistan is predictable and reducible. By combining technology, behaviour change, and city-led action, these South-Asian cities can protect their residents and save millions of lives each year. Smarter forecasting, clean mobility, and data-driven exposure interventions offer a path forward. Winter smog no longer needs to be an annual health crisis; with change it can be a manageable challenge.

Caroline Graybill overseen by Louise Thomas

.svg)